Helvellyn

How an evening run got me thinking about spirituality

I’ve known Sarah for a while. First through the wonderful wild world of Instagram, then more directly when she asked me to be her running coach. We worked together on and off for about three years, through all the highs and lows that running brings and became friends in the process. Like many of the runners I coached, we stayed in touch after I closed the doors on my coaching business last year. So when I was back in the Lake District recently, we made a plan to head into the fells together for a proper catch-up.

Before we met up, I asked if there was a fell or trail she especially wanted to run. Somewhere that maybe meant something to her or a place that keeps drawing her back. This was her response:

“Helvellyn always feels like a bit of an anchor, with many evening & first light runs on or around the mountain. Squeezing in mini adventures around work (for some reason Helvellyn often feels like the target summit), the anticipation of longer evenings creeping back in, BG support etc.”

It made me smile, because if someone had asked me the same question, I would have chosen Helvellyn too. I’m not even sure why. Maybe it’s because I can picture its contours so clearly, or because I can feel the texture of the rock on its ridge scrambles if I close my eyes. Maybe it’s the stories my dad used to tell me about the adventures he’d had there. Whatever it is, the mountain has lodged itself in my subconscious and I smile when I think of it. And I suspect I’m not the only one. I have no doubt that there are hundreds, if not thousands of people who live in or have visited the Lake District who feel the pull of Helvellyn.

That day, running with Sarah, I started to reflect on why this mountain brought up these feelings. Why does this particular mountain feel different? And why, when I talk about Helvellyn, do I not speak about it in the same way that people in other parts of the world speak about their mountains?

Mount Kailash in Tibet, Mount Fuji in Japan—these are not just peaks on a map. They are living presences. People have walked towards them and around them for thousands of years, carried by faith, ritual, and a deep spirituality. Yet here in the UK, or even in most of Europe, we don’t seem to have that kind of relationship with our environment anymore. If I told you that I was going to spend a couple of weeks walking around Helvellyn, quietly muttering mantras, all because I was seeking out enlightenment, you would label me as a bit odd and irrational. But when we see a picture of a brown person blessing mountaineers about to embark on a long climb up Everest we enjoy the exoticism. We understand that climbers are there to conquer a peak rather than form a relationship with the mountain and be closer to god, but we are happy to let the locals perform their rituals for our cameras. (And we also don’t question the fact that Everest is not the real name of the mountain, it is a colonial name given to the peak without any permission.)

When white people started to rape and pillage their way around the world we took it upon ourselves to look down at people who experienced spirituality differently to us, labelling them primitive, irrational, unscientific. While at the same time, we romanticised them. The figure of the monk in the Himalayas or the shaman in the Andes became something to marvel at, a curiosity for Western travellers to write home about while our colonial systems actively set out to dismantle those same traditions.

I remember a few years ago in Nepal, hiking up to a cave to be blessed before crossing a high mountain pass. It was a powerful experience, but if I’m honest, I still treated it like a novelty. Something to collect. A story to tell. It is uncomfortable for me to recon with and it says a lot about the lens I’ve been taught to look through: one that ranks spirituality depending on who performs it and where.

Hundreds of books, films, stories and conversations have taught us to see Indigenous or non-Western practices as “authentic spirituality,” while dismissing the possibility that our own landscapes could hold anything similar. It keeps us fascinated by ceremonies in the Himalayas while laughing off the idea that an English fell runner might bow their head for a blessing before a climb. We end up holding other people’s reverence at arm’s length—beautiful to look at, but never to be taken as seriously as our science or our logic.

Western rationality has been elevated as the highest form of thought, the gold standard by which everything else is judged. Spirituality tied to land is tolerated only when it appears in places we’ve already decided are “exotic.” The irony is that so many Westerners now travel to these “exotic” places precisely to feel something sacred and spiritual. To chase meaning or mindfulness in landscapes that still carry ancient rituals. That’s not just spiritual tourism, it’s neo-colonialism, where other people’s sacred spaces become our personal recharge stations.

As I understand it, Europe had its own traditions of reverence before the Enlightenment erased them. Our mountains had their gods and spirits, we had places where offerings were left and stories rooted. That history has been overwritten so thoroughly that we now forget it ever existed. Science has taken the place of our lost reverence, and our entrenched racism has made sure it’s here to stay.

It is not just through our colonial past and deep seated racism that we have lost touch with our own nature. I feel like capitalism has to take a lot of the responsibility too. We have reframed mountains as resources to be mapped, conquered and exploited. Even in the outdoor sports world, the language gives it away: conquer, summit, first ascent, fastest known time. Mountains become challenges to dominate, lists to tick off, adventures to brag about.

We talk about “doing” the Alps or “bagging” Munro’s. Even National parks, while trying to protect landscapes, often package them into consumable “experiences.” Adventure brands push the message that value comes not from simply being in the mountains, but from maximising what you can get out of them: speed, elevation, gear, content.

It’s the same story of extraction and exploitation, just dressed differently. Where we once cut down all the trees for fuel and to make way for farming, we now mine the landscape for selfies and strava segments, reducing the mountain to proof of our own effort. Even our sense of achievement is framed in capitalist terms: personal bests, vertical metres gained, segments conquered. Reverence becomes performance.

Personally, I think I need to start the work of how to shrug off this racist and capitalism mindset that has formed the way I see nature in our (Western) backyard. That doesn’t mean I am going to start copying ceremonies from other cultures or stop pressing “start” on my GPS watch when I head out on the trail. I think the work starts in remembering that we too used to have a deeply spiritual connection with nature and we can let ourselves feel that again without thinking that it is sentimental or unnatural.

If I am honest with myself, I know that I feel it. I know there is something about being in these places, I just let “rationality” get in the way of exploring these feelings. I really do think that we are all losing out on a deeper and more enjoyable connection when we see mountains and nature as simply “playgrounds” or experiences to collect.

We have traded connection for content, rituals for “progress”, reverence for science. We have made ourselves feel superior to the rest of the world and in the process we have lost one of the most important things about being human — our inexplicable link to the natural world.

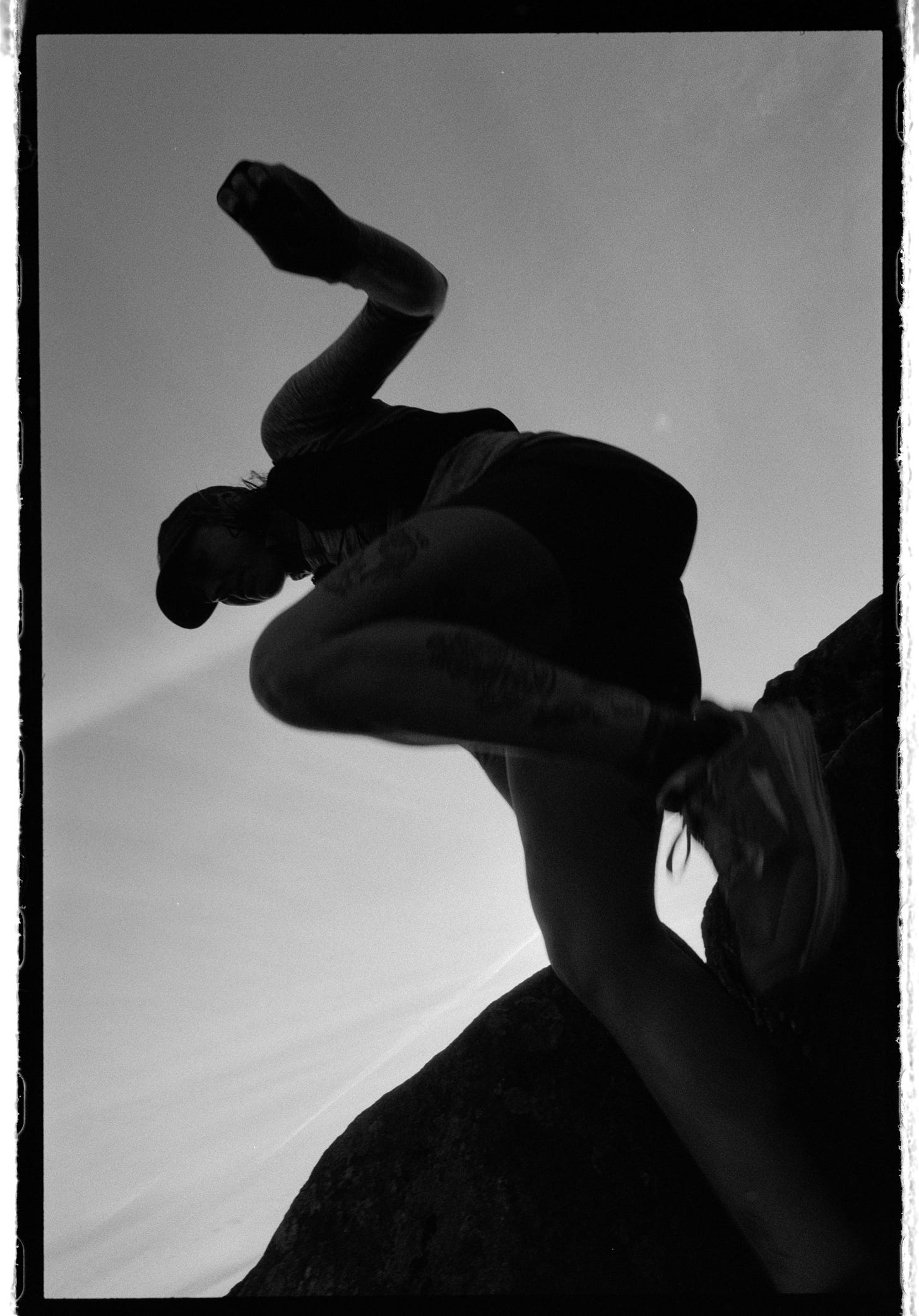

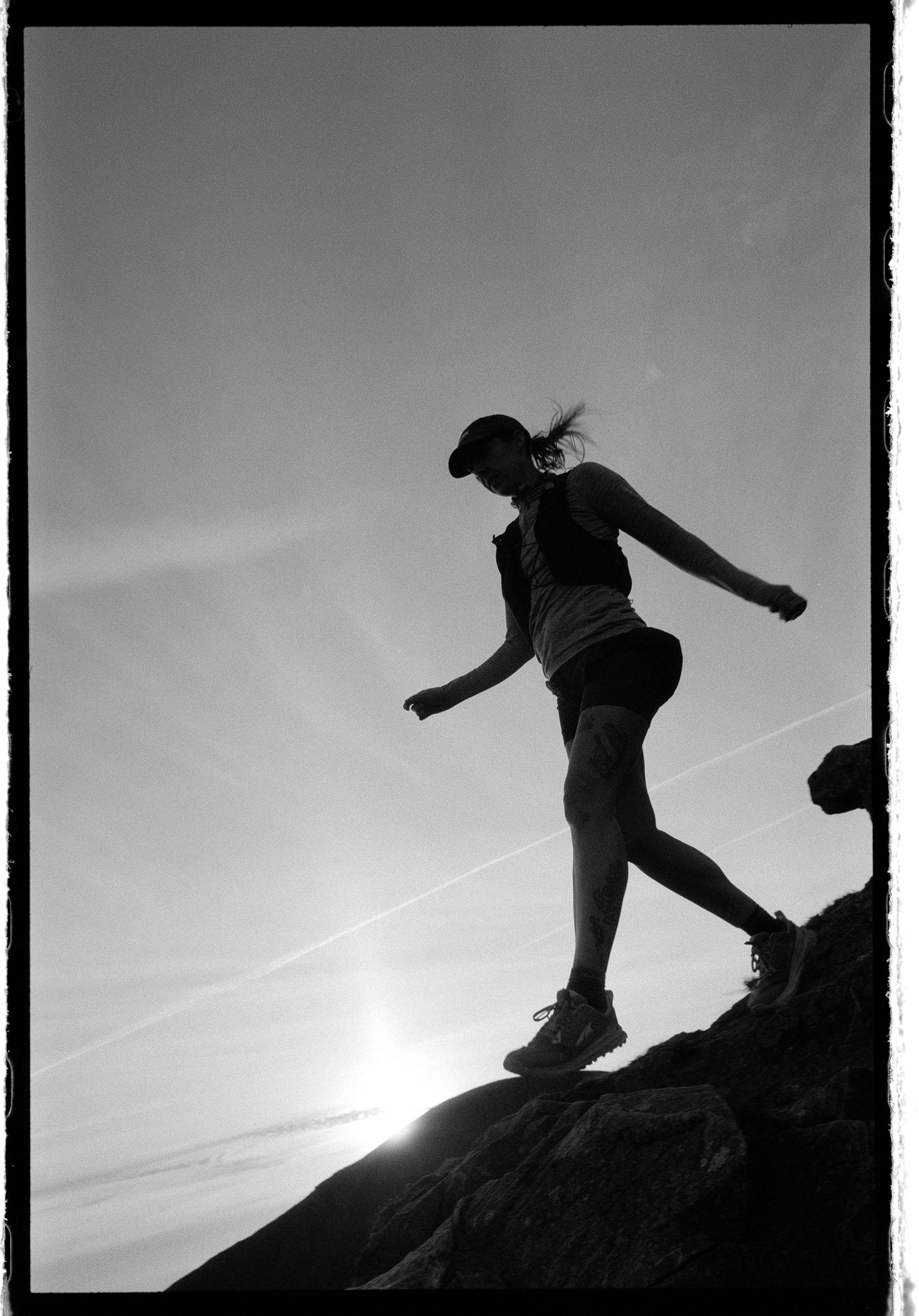

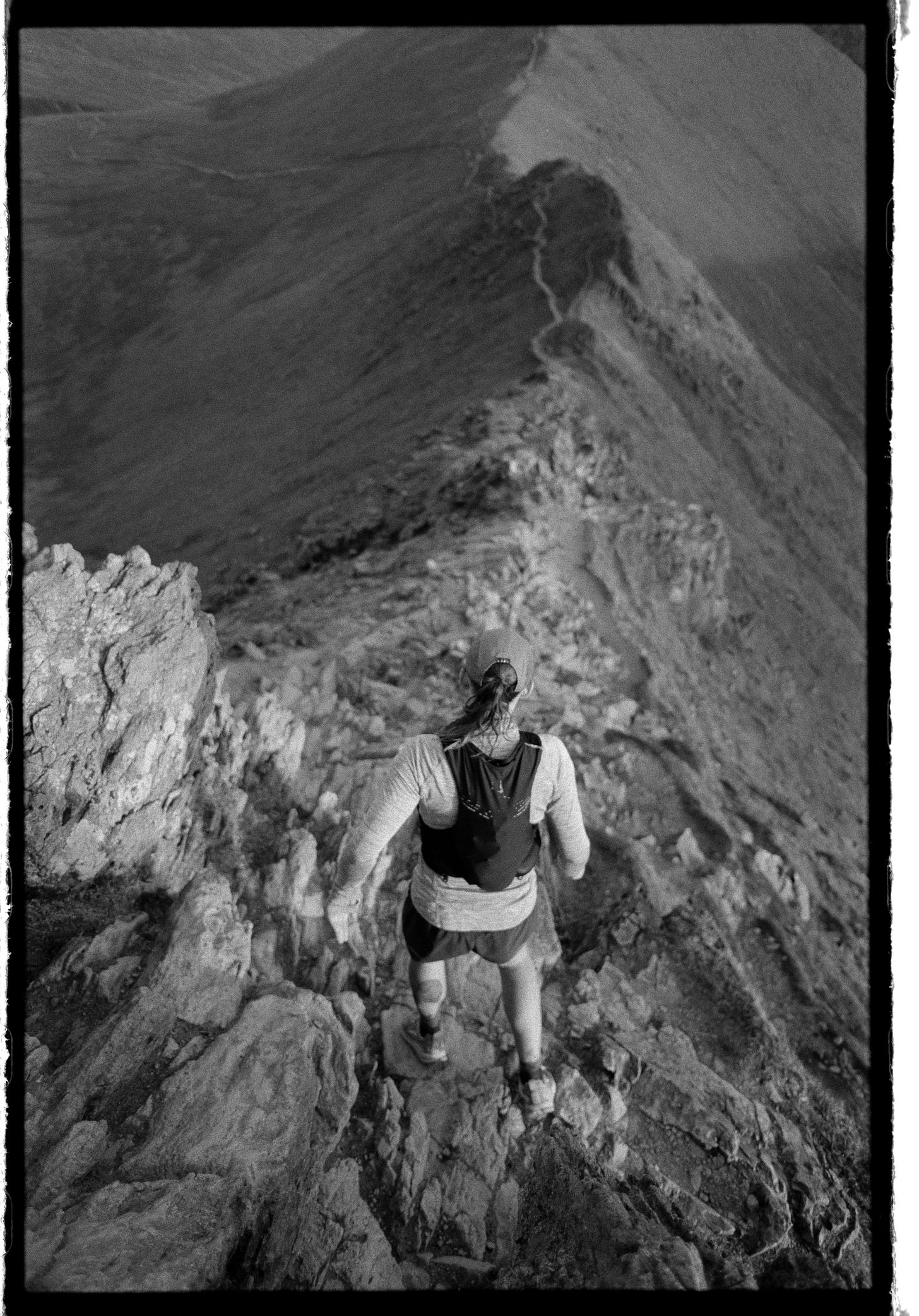

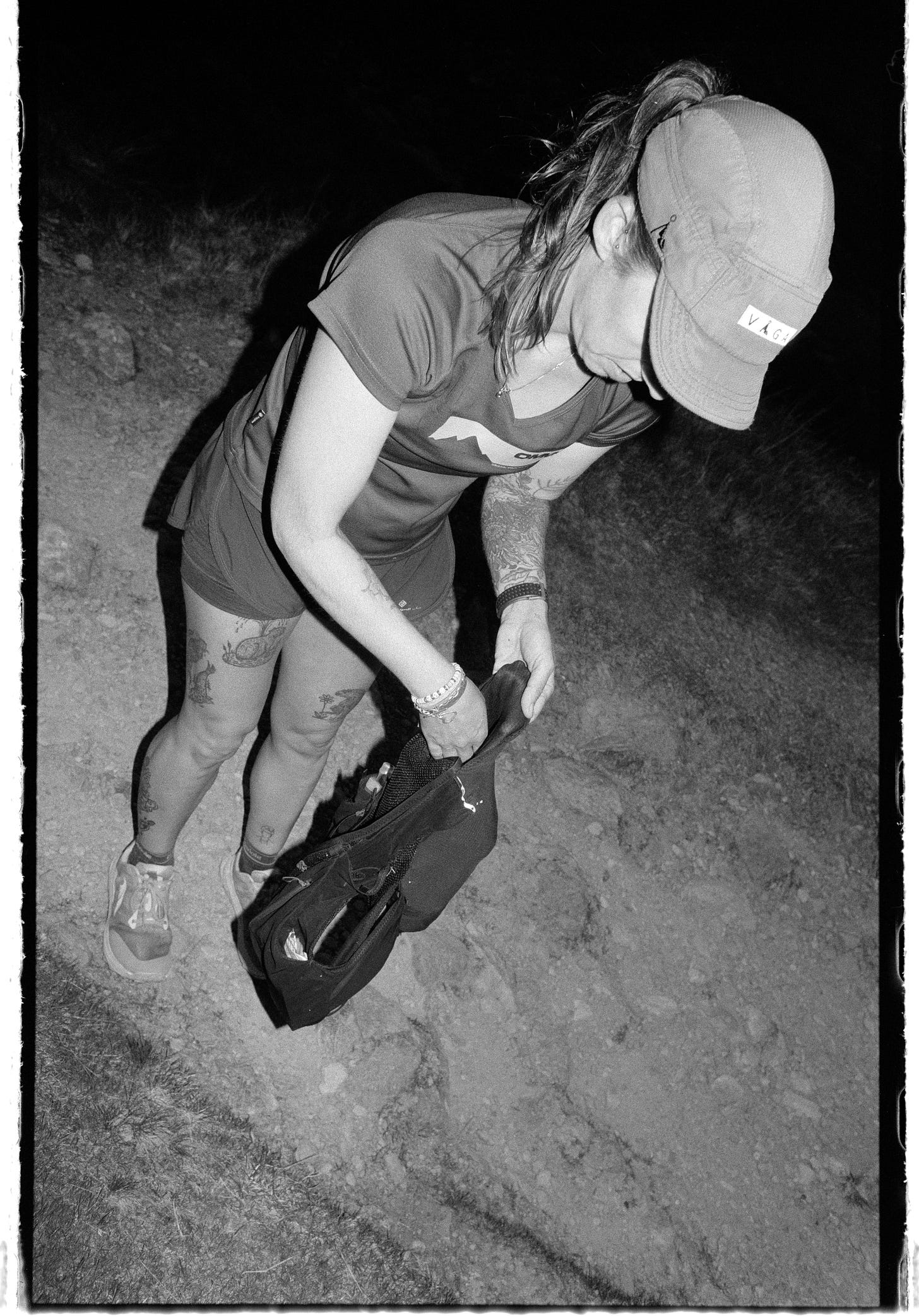

Here are a few photo’s from that lovely evening out on Helvellyn with Sarah that sparked all these thoughts:

So much this. I think about these topics constantly – how Enlightenment thinking poisons the well of what we call the 'outdoors'. But equally I think a counterculture of Romanticism is brewing. Demons grow bold and hungry in the machine. Meaning can be found beyond it, and places are once more enchanted.

You capture so well the strange mix of familiarity and awe we can feel for a mountain - you don’t need performative guilt as a framework to write about it.

A spiritual relationship with the natural world hasn’t been erased in the West, it has simply evolved (as it is evolving everywhere). Europe has its own traditions of sacred landscapes streching back over millenia, albeit expressed in folklore and art rather than mainstream religion. From Celtic hill shrines, Norse mountain myths and Christian pilgrimages to Romantic poetry and Re-wilding, that lineage hasn’t vanished; and your writing is part of it.

It’s also worth remembering that novelty and stereotype biases are universal, not unique to “white people” or Western culture. The rational-West vs. spiritual-non-West framing is a false dichotomy and isn't supported by history. Across time, utility and conquest have shaped our species' relationship with nature, just as much as awe and spirituality have. Colonialism, capitalism and science have blunted our emotional connection to the landscape around the globe but they haven’t erased it.

I think your gift as a writer is helping people remember that connection isn’t something we need to borrow from elsewhere - it’s here, waiting for us, if we pause long enough to recognise it. Reading your piece reminded me of the deeply spiritual times that I have spent in nature, some of those, on or around Helvellyn. Your voice is powerful when it leans into that wonder.

Rather than adopting a stance of moral outrage or cultural self-loathing, why not consider what traditions of reverence might we recover, or what modern rituals we could create?

Sometimes the best advice is simply to think less while you wonder more.